2026 Redistricting: A Messy, High-Stakes, State-by-State Scramble

Court fights, ballot measures, and dueling gerrymanders are reshaping the map

There’s been a steady drumbeat of coverage over the past year about how Republicans, encouraged by the Trump White House, have pushed hard for mid-decade redistricting to make it harder for Democrats to win enough districts to flip the House even if Democrats win the majority of US House votes in 2026. Generally, House redistricting only happens after each Census, in years like 2012 and 2022, but that’s more of a norm than a hard rule. There are mechanisms in place for states to redraw their maps mid-decade, and Republicans (and later Democrats) have tried to use that flexibility to add new aggressive gerrymanders in the frantic arms race. Since winning a seat is all that counts, not the margin, gerrymandering lets a party draw districts that distribute its voters more efficiently and tilt the map in its favor. This creates what’s often called “structural bias,” where a party can win a majority of US House seats without winning a majority of US House votes. In 2024, for example, Trump won the median House seat by 3.1% even though he only won the national vote by 1.5%, meaning the House map had an R+1.6 structural bias. With new gerrymanders in a handful of other states, Republicans aimed to push that advantage closer to four or five points.

Texas was the centerpiece of that strategy. Gov. Greg Abbott and Texas Republicans passed an aggressive new gerrymander that, if implemented, would likely shift three to five seats from blue to red. Republicans moved quickly in other states as well, enacting more favorable maps in Ohio and North Carolina and pursuing a similar push in Florida, Missouri, and Indiana.

Democrats, of course, weren’t going to sit still. In California, Gavin Newsom pushed through Prop 50, replacing the state’s relatively fair commission-drawn map with a partisan Democratic gerrymander that effectively offsets the gains Republicans hoped to lock in with the new Texas map. And in Virginia, after winning full control of the state government in 2025, Democrats now look poised to draw a very aggressive map that could flip three to four seats blue.

A big twist came yesterday: a panel of federal judges blocked Texas’s new map from being used in 2026. State officials immediately appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and I think it’s more likely than not (but far from certain) that the Court issues some sort of stay that keeps the Texas map in place. Even so, the momentum has shifted. With Democrats picking up wins in CA, VA, and UT, the overall picture looks much less like a Republican firewall and much more like a chaotic, state-by-state scramble that could end up benefiting Democrats just as much—or even more—than Republicans.

2026 US House State of Play

What This Chart Shows

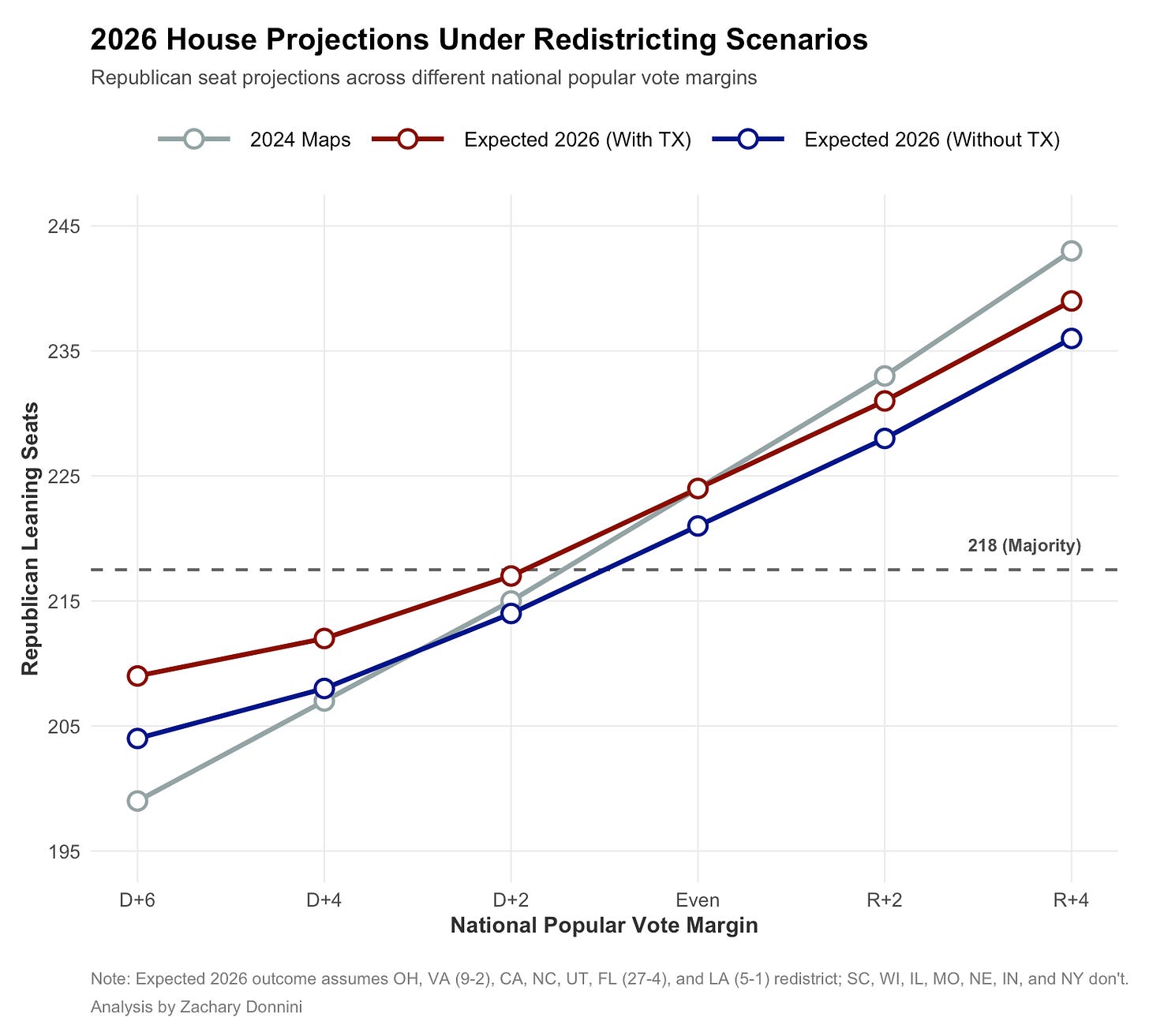

This chart projects how many House seats would lean towards Republicans in 2026 under different electoral scenarios and redistricting outcomes.

The X-axis (bottom) shows the national US House vote margin—ranging from Democrats winning by 6 points (D+6) on the left to Republicans winning by 4 points (R+4) on the right. “Even” means a tied national vote.

The Y-axis (left side) shows the number of House seats Republicans would be expected to win out of 435 total. The dashed line marks the majority threshold—whichever party gets 218 or more seats wins control of the House.

The three lines represent different map scenarios:

Gray (2024 Maps): The maps used in 2024

Red (Expected 2026 With TX): Expected 2026 maps if Texas redistricts along with OH, VA, CA, NC, UT, FL, and LA

Blue (Expected 2026 Without TX): Expected 2026 maps if Texas doesn’t redistrict while OH, VA, CA, NC, UT, FL, and LA do.

Key Takeaways

The Mid-Decade Redistricting Arms Race Is On Track to be a Wash

To measure the structural bias of the House under each scenario, you can look at where the lines cross the 218-seat majority threshold. On the 2024 maps (the grey line), that crossover happens at roughly D+1.6 (R+1.6 structural bias), meaning Harris needed to win the national popular vote by about 1.6 points to carry a majority of House districts. The expected 2026 maps with Texas’s new gerrymander (the red line) push that bias to about R+2, while the scenario without Texas (the blue line) brings it closer to R+1.

Texas is the biggest swing factor in the mid-decade redistricting cycle, but the overall effect is on track to be roughly a wash. Whether the new Texas map survives or not, the structural bias of the expected 2026 landscape—if applied to 2024-level results—ends up looking pretty similar to the bias we saw under the 2024 maps. In other words, neither party is on track to gain much structural advantage from redistricting alone heading into the midterms.

Mid-Decade Maps Are Making the House Less Competitive Than Ever

Redistricting after the 2020 US Census was already packed with aggressive gerrymandering on both sides, and while this gerrymandering largely canceled out in partisan terms, it sharply reduced the number of competitive seats. This second round of mid-decade redistricting has pushed states even further: both Democratic and Republican legislatures have adopted more severe maps that again mostly offset each other, but further shrink the pool of competitive districts. In the figure above, you can see this in the red and blue lines—both are noticeably flatter than the grey line—meaning the number of seats that could realistically swing between a strongly Democratic year and a strongly Republican one is much smaller. The battleground will be narrower than ever, and the House will almost certainly be decided by extremely tight margins, even after accounting for the national political environment.

Too Many Unknowns to Call the Fight Yet

It’s still highly unclear which states will even be allowed to redraw their maps, given the mix of ongoing federal court battles, the possibility of Supreme Court overrides, potential ballot measures, state legislatures deciding whether to join the national redistricting push, and the still-pending Section 2 Voting Rights Act ruling in Louisiana v. Callais. As of November 19, Kalshi shows nine different states with between a 20 to 80 percent chance of redistricting again before the 2026 elections. There are many independent events that could break better for Democrats or Republicans, but the key takeaway from our current trajectory is twofold: (1) we’re heading toward a very similar, slightly Republican structural bias as we saw in 2024, and (2) we’ll see a massive decline in competitive general elections due to increased gerrymandering across the country.