Low Turnout, High Stakes

Democrats keep winning low-turnout specials like next Tuesday’s in Florida and Wisconsin — a pattern that’s intensified since Trump returned to power

On Tuesday April 1st, a few high-profile elections will take place that are drawing significant media attention and campaign spending. They’re widely seen as an early referendum on the first months of Trump’s third presidential campaign. Two U.S. House seats in deep-red districts in Florida are up for grabs, and if Democrats manage to flip one (which is unlikely), it would narrow the GOP’s House majority from three seats to just two. Republicans are clearly feeling the pressure. They were so concerned about protecting their narrow House majority that they pulled Elise Stefanik’s nomination to be U.S. ambassador to the UN — just to avoid triggering a special election in a district Trump carried by 21 points last November. Meanwhile, in Wisconsin, a hotly contested State Supreme Court seat is going to end up with $100 million in total spending — with Elon Musk playing a surprisingly active role.

These races come on the heels of a string of special elections for state legislative seats, where Democrats have been performing exceptionally well. On average, Democratic candidates have outperformed Kamala Harris’s 2024 showing by 12 points, including a headline-grabbing flip of a State Senate seat in central Pennsylvania that Trump carried by 15 points last November. But, to be clear, this trend isn’t new — Democrats have been dominating in low-turnout elections for over a year and a half now.

I broke down these recent Democratic overperformances and previewed Tuesday’s special elections during my segment on NewsNation on Friday. You can watch the full clip here, especially if you’re interested in the Florida specials.

A Brief History of Voter Turnout Dynamics

For decades, political analysts and strategists believed that higher voter turnout favored Democrats, based on the assumption that nonvoters—often younger, lower-income, and more racially diverse—were more likely to support Democratic candidates. This idea became particularly salient during the Obama years, when Barack Obama's 2008 campaign mobilized millions of new and infrequent voters. Black voter turnout reached a historic high, matching white turnout for the first time, and surged in key swing states, helping Democrats win the presidency and make gains down-ballot. The success of Obama-era turnout operations seemed to reinforce the longstanding belief that Democrats benefit from expanded access to the ballot.

Republicans have historically tried to take advantage of the idea that the electorate in lower turnout elections would be more conservative, while liberals have complained about it as disenfranchisement. Georgia’s runoff rule, which requires a candidate to win a majority of the vote to avoid a runoff, dates back to 1964. It was implemented by segregationist Democrat Herman Talmadge to dilute Black voting power after the Supreme Court’s one person, one vote ruling. More recently, Georgia Republicans have maintained and adjusted the rule—most notably shortening the runoff period in 2021—amid criticism that it disproportionately affects minority voters and can suppress Democratic turnout in high-stakes races.

Changing Coalitions

I’ve been tweeting about this nonstop, but it’s worth emphasizing again: since 2020, we’ve been living through a major political realignment. Republicans have made significant gains with voters of color, particularly Hispanic and Asian voters, who tend to have lower turnout and political engagement. At the same time, Democrats have improved with well-educated White voters, who historically turn out at much higher rates.

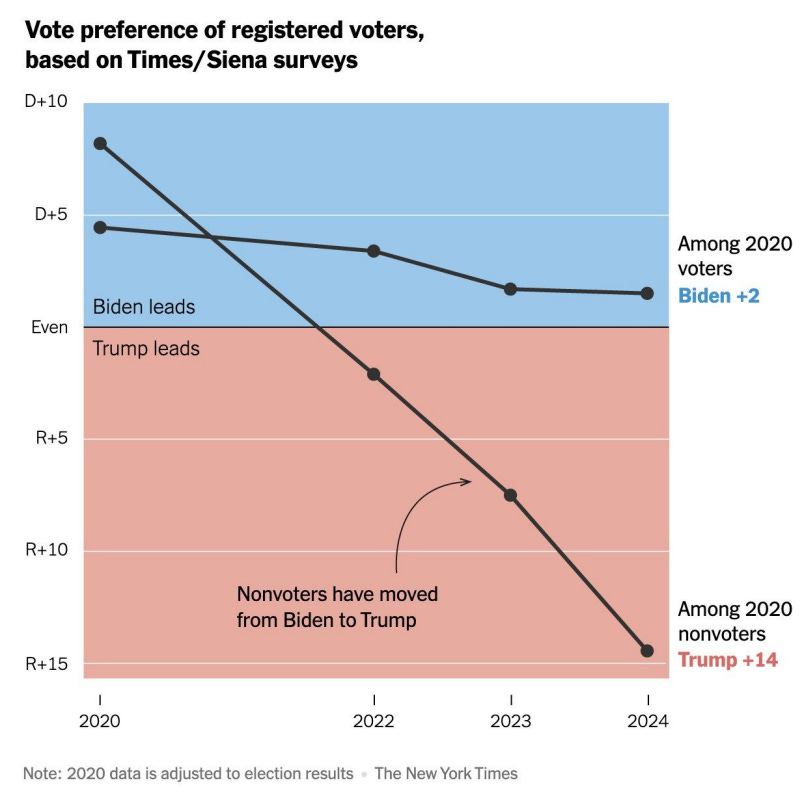

I'm including one of the most insightful charts I came across last year — one I cited constantly throughout the summer and fall of 2024. It shows that high-engagement Americans, those who voted in 2020, didn’t shift much at all between 2020 and 2024. But among low-engagement Americans, meaning those who sat out in 2020, the movement was dramatic: a sharp swing from Blue to Red in just four years.

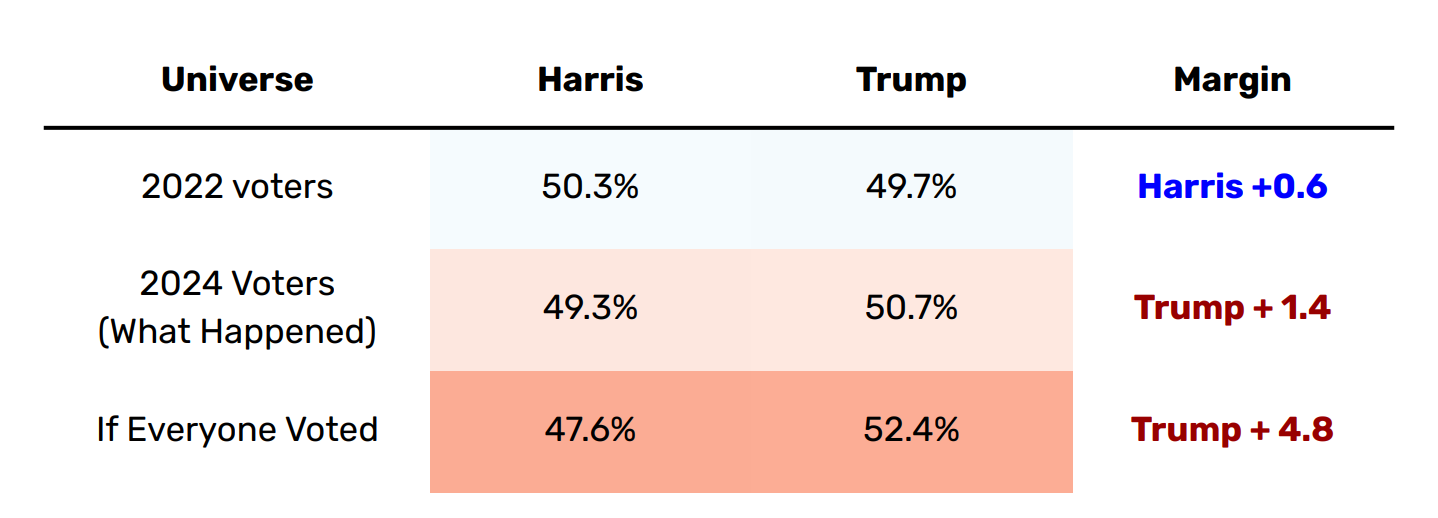

David Shor of Blue Rose Research estimates that if every eligible voter had cast a ballot in 2024, Trump would have defeated Harris by about 5 points, rather than the actual margin of 1.4. In other words, the race was only close because many conservative-leaning voters — particularly those with lower turnout propensity — stayed home. One particularly striking detail from the same analysis: the 2022 midterm electorate was roughly two points more Democratic than the 2024 electorate, despite 2022 being a relatively strong cycle for Republicans, who gained seats in the US House as the opposition party.

Broadly speaking, we’re moving toward a dynamic where lower-turnout elections tend to favor Democrats. If everyone voted, this would be ideal for Republicans. Their best-case realistic scenario is a high-turnout presidential election, with midterms coming in a close second. But the further turnout drops — especially in these random special elections — the more the environment tilts toward Democrats. This pattern is particularly visible in the ultra-low-turnout special elections we’ve seen recently. Democrats tend to thrive in these contests, especially in lower-profile races like state legislative specials, where media attention is minimal and the electorate skews more engaged and left-leaning.

What does this mean for 2026 or 2028?

Democrats have been performing well in recent special elections, and they’re likely to notch more wins on Tuesday — potentially flipping the Wisconsin Supreme Court seat and racking up a major overperformance in Florida. But I’d be cautious about reading too much into what that means for 2026 or 2028.

Historically, special election results have been a pretty good indicator of the national political environment heading into the next general election. But that pattern broke down in 2024. Democrats ran up the score in specials throughout 2022 (which I wrote about here), 2023 and early 2024, only for Harris to flop against Trump in November. Why? Because the electorate in these really low turnout specials is fundamentally different from the one that shows up in higher-turnout elections.

Right now, the highest-propensity voters in the country are disproportionately well-educated, white, and left-leaning — the kind of "resistance liberal" Democrats who are especially activated when Trump is back in the spotlight. They dominate special election turnout, but they don’t represent the full electorate you see in a midterm or presidential cycle.

There are still good reasons to think Democrats could do well in 2026 — most notably the historical trend that presidents almost always take a hit in their first midterm, and some lukewarm public reception to early moves by the Trump administration. But I wouldn’t count great special election results as one of those reasons. The Democratic edge in these contests feels more like a structural feature of the current turnout dynamics than a sign of broader political momentum. It’s getting a bit ridiculous at this point after Trump’s victory — and a close race in FL-06 on Tuesday would only add to the surprise. But it’s worth keeping perspective.